The 10 Best Films of 2004 (and Five of the Worst)

Let's start off by being honest: I haven't seen every movie that's come out this year, so I can't possibly tell you

exactly which were the ten best. Moreover, many of the films being hailed by critics in LA, NY and overseas as "the year's best" haven't even gotten around to Orlando yet. But even if I had somehow seen them all, it would

still only be my opinion, which is by no means assured to be the general view of a particular film. Thus, all you're getting here is the best of what I saw, which is most of the major films. It has to be said that some local critics disagreed with me on some choices (notably

Dogville), but I stand my ground.

Even though critics sometimes disagree, as they sit down to write up their 10-best lists each year, a consensus forms among the "name" movie critics because once a film has picked up some honest buzz (as opposed to film-industry hype), they make a point of seeing it.

It should also explain why some films the critics hate do pretty well, or films the critics love do poorly: film reviewers are desperate for films that show them something they haven't seen a thousand times. Unlike the public, who don't see 100 or more movies a year, film critics see the predictable and mundane, the poorly-cast or deeply flawed with much greater frequency, and thus are a lot less forgiving of hackery than the general public.

By contrast, when a unique film comes along, critics can often champion them, overlooking minor defects that nonetheless fail to win over the public at large. Last year's

Girl With A Pearl Earring is a perfect example: critics saw a gorgeous, beautifully-cast whimsical invention that fleshed out a historical mystery; audiences saw a beautiful -- but empty and slow-moving -- snoozefest.

Unlike some other critics, I never rank films in terms of preference. Here's ten movies I saw that I thought were really wonderful -- a few you probably saw, most you didn't, in no particular order.

•

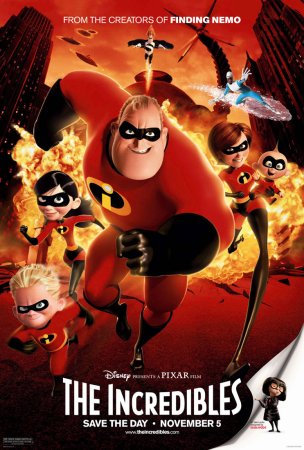

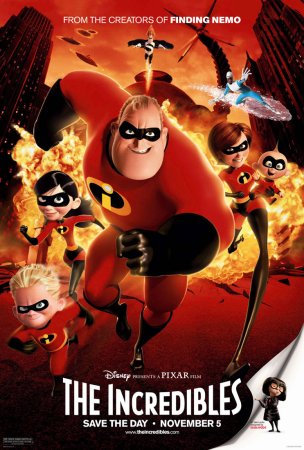

The Incredibles -- the clear winner in the animation category, people tend to overlook that this (along with the rest of Pixar's body of work) is also a terrific movie on every level. Edna Mode, the superhero costume designer, is by far the most original (and hilarious) character of the year. Yes, the computer animation continues to dazzle, but the real secret of Pixar's success is pushing some heart and soul into those pixels. Again and again and again.

•

Ray -- it's always heartening to see a biopic get some mainstream attention, and few deserve it more than this picture, which benefits both from the rich life of its subject and the superb performance of Jamie Foxx in the lead role. Director Taylor Hackford makes the wise decision to depict Ray Charles' good

and bad sides, a risk given his beloved public persona, but a move that gives the film a depth and feeling that reflects Charles' music.

•

A Very Long Engagement -- rather unusually this year, there's not a lot of foreign films in the top 10. This, however, is a lovely exception: a lovely French film (with subtitles) that tales a tale of two lovers since childhood, separated by war, and the one who seeks the other. The phrase "swept away" comes to mind, combining breathtaking photography with heartbreaking (and heart-stopping) moments from a fine cast. It's tough to be bloody and lyrical, but this one manages somehow.

•

Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow -- Imagine trying to make

Raiders of the Lost Ark in your garage, with only bluescreens. For that alone, this film is a remarkable achievement. I've got a weak spot for movies that take me somewhere I've almost, but never quite, been. This one did the trick, transporting the audience back to a 1940s that only existed in

art noir comic books and futuristic pulp novels. Visually stunning, it's plot was kind of predictable, but that was hardly the point. I absolutely love this movie, despite the fact that I

loathe every single one of its marquee stars.

•

Fahrenheit 9/11 -- Some people are almost violently alienated by Michael Moore's films, mostly because he reminds people of uncomfortable truths they'd rather sweep under the rug, but also in part because they are wildly (and often willfully) misunderstood, particularly by those who haven't seen them (don't believe me? Wait till you hear some Rethuglican call Moore "a fat slob" or something similar, and then check out the size of

their gut). Just as

Bowling for Columbine was emphatically not an attack on gun owners, neither is

Fahrenheit 9/11 a mean-spirited attack on President Bush. What both films

actually are is an exploration of how our media outlets increasingly ignore the real issues, conspire with those in power to hide the truth, and shamelessly manipulate the public with disinformation. But of course, the media either don't recognise that, or do recognise it and exact their revenge by mischaracterising the attacker. It will be interesting to see if Moore's next film -- said to be an exposé of the health care industry -- receives the same vitriolic venom from his current critics.

•

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban -- there are inherent and insurmountable problems in attempting to film a Harry Potter book: after the first one, the books became too long and intricate to boil down into a single film without cutting out huge chunks of plot, the effects department sometimes lets the audience down, and the leads -- wonderful as they are -- are rapidly aging themselves out of a job. All that said, new director Alfonso Cuaron has a deft touch with visuals and with the teen actors, really bringing out the best in them. The ending -- heck, the whole movie -- feels rushed, but most of it is the best stuff we've seen from this franchise since the first film.

•

House of Flying Daggers and

Hero -- I'm cheating a little here, combining two films into one entry, but it's the ultimate double feature: flying kung-fu dreamscapes deluxe. If you thought

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon was good, these two films go

way beyond that one. The stories strangely underserve the visuals, but if you're looking for an eye-popping good time, skip the awful

Alexander or the terrible

Troy and go for these epics instead.

•

Monster and

Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer -- again with the double feature, but these two are linked to the point of being joined at the sprockets. Aileen Wournos' life, murders and death are all examined, in

Monster by the incredible in-her-skin performance of Charlize Theron and in

Life and Death by a director who can claim a sort of friendship with the serial killer. Both are riveting, like a road accident you can't look away from.

•

End of the Century: the Story of the Ramones -- even if you've never heard of the Ramones, this is an invaluable slice of music history that until recently was under-chronicled. The film could easily have been subtitled

How We Invented Punk Rock and Changed Music Forever, their influence was really

that large on the last hurrahs of modern rock. A rare peek inside the minds of the band that was "Too Tough to Die."

•

Festival Express -- I'll end this list with a film I personally didn't care for, but which I appreciate for the impact it has on people from "back in the day" and which has incredible value both for its backstory and its historical significance.

Festival Express is a documentary made in 1970 and trapped in litigation ever since, featuring interviews, candid moments and performances never seen before from some of the biggest names of the just-post-Beatles era. The big draw for American hippies is the heretofore unscreened moments with Jerry Garcia, The Band, and Janis Joplin, but there's plenty more for fans of that era. In some ways this is the ultimate "stoner movie," since both the audience and the stars of the film have a definite familiarity with the excesses of the era.

There are of course many, many great films that didn't make the cut here, including

The Dreamers, Napoleon Dynamite, Sideways, Supersize Me and

Finding Neverland, among others. Overall, I'd have to say it was a fair year for movies -- as opposed to 2003, which was a really fantastic year.

And now, as they say, for something completely different:

Five Truly Terrible 2004 Movies

Gothika - More funny than scary. If you're a horror movie, that's a bad thing. Worse, it was Halle Berry's return to the screen after winning an Oscar for

Monster's Ball. This and

Catwoman might just put an end to her movie career.

Johnson Family Vacation -- Whoever thought an all-black ripoff of

National Lampoon's Family Vacation was a good idea should be slapped. Repeatedly. With a frying pan. Manages to demean and insult

both whites and blacks, to say nothing of Missouri (which may never recover).

Dogville -- My lord, this was awful. Nicole Kidman plays Jesus, I mean Everyman, in this Biblical morality play a la "Our Town." The sparse, theatrical staging may seem novel (unless you've seen any

plays in your life), but the film is unrelentingly unpleasant, excessively cruel, and patently obvious in its "twists."

White Chicks -- Amazing makeup. That's all, though.

Catch That Kid -- Even though one has to accept a certain amount of ridiculousness in a film aimed at children, this one crossed

way over the line of stupidity, mediocrity and inanity. The plot machinations are absurd, the kids themselves are studiously over-directed, the implications of the film are horrific ... everything about this is just awful. Frankie Muinz's

Agent Cody Banks 2 looks like

Citizen Kane by comparison.

Just in the nick of time, the March episode of Chas’ Crusty Old Wave is available for download either via the website or directly from iTunes. This episode features a focus on Elvis Costello’s “Brutal Youth” album, some rants against the then-new teen curfew in downtown Orlando, and best of all, Liz Langley's hi-larious Horror-scopes.

Just in the nick of time, the March episode of Chas’ Crusty Old Wave is available for download either via the website or directly from iTunes. This episode features a focus on Elvis Costello’s “Brutal Youth” album, some rants against the then-new teen curfew in downtown Orlando, and best of all, Liz Langley's hi-larious Horror-scopes.

• A Very Long Engagement -- rather unusually this year, there's not a lot of foreign films in the top 10. This, however, is a lovely exception: a lovely French film (with subtitles) that tales a tale of two lovers since childhood, separated by war, and the one who seeks the other. The phrase "swept away" comes to mind, combining breathtaking photography with heartbreaking (and heart-stopping) moments from a fine cast. It's tough to be bloody and lyrical, but this one manages somehow.

• A Very Long Engagement -- rather unusually this year, there's not a lot of foreign films in the top 10. This, however, is a lovely exception: a lovely French film (with subtitles) that tales a tale of two lovers since childhood, separated by war, and the one who seeks the other. The phrase "swept away" comes to mind, combining breathtaking photography with heartbreaking (and heart-stopping) moments from a fine cast. It's tough to be bloody and lyrical, but this one manages somehow.

• Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban -- there are inherent and insurmountable problems in attempting to film a Harry Potter book: after the first one, the books became too long and intricate to boil down into a single film without cutting out huge chunks of plot, the effects department sometimes lets the audience down, and the leads -- wonderful as they are -- are rapidly aging themselves out of a job. All that said, new director Alfonso Cuaron has a deft touch with visuals and with the teen actors, really bringing out the best in them. The ending -- heck, the whole movie -- feels rushed, but most of it is the best stuff we've seen from this franchise since the first film.

• Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban -- there are inherent and insurmountable problems in attempting to film a Harry Potter book: after the first one, the books became too long and intricate to boil down into a single film without cutting out huge chunks of plot, the effects department sometimes lets the audience down, and the leads -- wonderful as they are -- are rapidly aging themselves out of a job. All that said, new director Alfonso Cuaron has a deft touch with visuals and with the teen actors, really bringing out the best in them. The ending -- heck, the whole movie -- feels rushed, but most of it is the best stuff we've seen from this franchise since the first film.

For what is I believe the 10th year running, I am attending and covering the

For what is I believe the 10th year running, I am attending and covering the  Tim Tom was the first of two stunning pieces of animation that blew the audience away. A cunning and incredibly stylish mix of computer animation and live action, the soundtrack (by Django Rheinhart!) blended perfectly with the piece in a polished, B&W homage to the Merrie Melodies style of slapstick.

Tim Tom was the first of two stunning pieces of animation that blew the audience away. A cunning and incredibly stylish mix of computer animation and live action, the soundtrack (by Django Rheinhart!) blended perfectly with the piece in a polished, B&W homage to the Merrie Melodies style of slapstick. Jumping back to traditional animation but with a delicious twist on the "women behind bars" genre was Penguins Behind Bars. Fish jokes abound, and the plot is played perfectly straight, but by making the characters all penguins, you get high comedy.

Jumping back to traditional animation but with a delicious twist on the "women behind bars" genre was Penguins Behind Bars. Fish jokes abound, and the plot is played perfectly straight, but by making the characters all penguins, you get high comedy. The Family Shorts finale'd with Lorenzo, the first new piece of strictly-traditional Disney animation in ages and quite possibly the best piece of cartooning they've done in-house in the last forty years. Yes, it's that good -- a stunning tour-de-force of music, animation and whimsy that recalls everything that used to be good and magical about Disney's unique brand of animation. Look for Lorenzo as the opener to a future Disney feature, but don't miss it if you'd like to see what Disney (even without Pixar) is really capable of when they try hard enough.

The Family Shorts finale'd with Lorenzo, the first new piece of strictly-traditional Disney animation in ages and quite possibly the best piece of cartooning they've done in-house in the last forty years. Yes, it's that good -- a stunning tour-de-force of music, animation and whimsy that recalls everything that used to be good and magical about Disney's unique brand of animation. Look for Lorenzo as the opener to a future Disney feature, but don't miss it if you'd like to see what Disney (even without Pixar) is really capable of when they try hard enough.